Panasonic Lumix G9II Review: A Photographer's Perspective

After two years of shooting with the original Panasonic G9, I finally made the upgrade to the G9II. Let me tell you, the decision wasn't as straightforward as you might think. The G9 had become an extension of my hand—every button, every dial mapped perfectly into my muscle memory. But technology marches forward, and the promise of phase-detect autofocus, better high-ISO performance, and that intriguing HHHR mode eventually won me over. So I bought it, took it into the field, and spent months putting it through its paces. This isn't a spec-sheet regurgitation; this is what it's actually like to shoot with the G9II as a stills photographer who couldn't care less about video features.

First Impressions: Something's Different, But the Image is Glorious

From the moment I unboxed the G9II, my brain knew something was off. My hand reached for controls that weren't there, my thumb searched for dials that had moved. Despite these initial ergonomic hiccups, which I'll dive into later, the first images I pulled off the sensor erased any doubts. The picture quality is simply outstanding—beyond praise, really. Colors? Classic Panasonic excellence, no caveats needed. That signature color science that made me fall in love with the system remains intact, rich and true without that artificial digital feel some brands struggle with.

The star of the show, even in these early tests, was the HHHR mode. I'll dedicate a full section to it later, but know this: it's a game-changer that Panasonic oddly whispers about instead of shouting from the rooftops. More on that soon.

Before we dive into the real-world experience, here's what you're working with under the hood:

- Sensor: 25.2MP Live MOS Micro Four Thirds sensor (up from 20.3MP in the G9)

- Image Processor: Venus Engine

- Autofocus: Hybrid Phase-Detect AF system with 779 phase-detection points plus DFD contrast AF

- Image Stabilization: 8-stop Dual I.S. 2 (sensor-shift + lens stabilization)

- ISO Range: 100-25,600 (expandable to ISO 50)

- Continuous Shooting: 60 fps with AF-S, 10 fps with AF-C (mechanical shutter)

- Shutter Speed: 1/8000s (mechanical), 1/32,000s (electronic)

- Viewfinder: 3.68M-dot OLED EVF with 120 fps refresh rate

- Rear Screen: 3.0-inch 1.84M-dot free-angle touchscreen

- Video: 5.7K 60p, 4K 120p (we'll leave it at that, since I don't shoot video)

- Storage: Dual SD card slots (both UHS-II compatible)

- Battery: DMW-BLK22 (new, higher capacity, backward compatible as power source)

- Connectivity: Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, USB-C (USB 3.2)

- Build: Weather-sealed magnesium alloy body

- Dimensions: 134.3 x 102.3 x 90.1 mm

- Weight: 658g (body only)

Let me cut through the marketing noise and tell you what really changed from the G9—both the meaningful upgrades and the "why did they bother" changes.

The Big Wins:

- Phase-detect AF finally replaces DFD-only system (more on this later)

- 25.2MP sensor vs. 20.3MP—a tangible but not transformational increase

- 8-stop stabilization vs. 6.5 stops, which is genuinely useful in real-world shooting

- 5.7K video if you care about that sort of thing (I don't)

- Dual UHS-II slots—both slots now support full speed, unlike the G9's UHS-I+II combo

- New battery with 20% more capacity and USB-C charging capability

The "Meh" Updates:

- Higher resolution screen (1.84M vs. 1.04M dots) that you'll hardly notice

- Slightly better EVF colors—nice but not worth upgrading for

- USB-C port replaces micro-USB, which should have been there years ago

The Downgrades That Actually Matter:

- No top LCD display—a real loss for quick settings checks

- 4K/6K Photo modes completely removed—taking Post Focus and in-camera Focus Stacking with them

- No stacked mode/drive dial - I really liked that layout

- No physical silent mode switch—a constant daily annoyance

- iAuto ISO removed—replaced with dumb Auto (more on this later)

The bottom line? Panasonic giveth and Panasonic taketh away. Some improvements are substantial, but you pay for them with lost features that made the G9 such a joy to use.

As always with camera reviews, I'll start with ergonomics because if a camera doesn't feel right in your hands, none of the specs matter. Here's where things get complicated with the G9II.

Panasonic made a curious decision here. The G9II is positioned as a professional camera—it's even called the Lumix G9 Mk II Pro and it's features are pro grade, but the body is borrowed from the Lumix S5 II, which is a mid-level camera, not a flagship. I'm still scratching my head over this choice. Yes, developing a completely new body costs resources, but they had the perfect template in the original G9. Instead, they went with the S5 II chassis, which brings both advantages and disadvantages. In my honest opinion, after months of use, the G9II body has more drawbacks compared to the G9 than benefits.

The grip itself is actually quite good—the camera hangs comfortably from relaxed fingers, allowing for hours of shooting with large lenses without fatigue. That's the positive. The negative? It's less "meaty" than the G9's grip, slightly narrower, which changes the position of my index finger. I have to bend it more to reach the shutter button, and after a full day of shooting, I notice the strain in a way I never did with the original G9.

In other part we see a great thing - the joystick, that was practically out of reach on G9, now, on G9II id placed perfectly - right under your thumb! I practically never used it on G9, but started dog so on G9II.

The front command dial around the shutter button is a massive improvement. On the G9, that dial felt like an afterthought—poorly positioned and hard to use. Here, it's large, tactile, and perfectly placed. I assigned exposure compensation to it, and for the first time in years, I'm actually using the front dial for that purpose instead of reaching for a button combination.

In exchange for that better front dial, Panasonic gave us the same awkward power switch placement found on their L-series cameras. It's on the right side of the top plate, and operating it with the hand that's holding the camera? Nearly impossible without shifting your grip. With the G9, I could power on the camera with one fluid motion as I brought it to eye level. Now it's a two-handed operation, and it feels like a step backward.

Here's where I get genuinely frustrated. On the G9, the mode dial and drive dial were stacked, giving us two displays on top—one for the mode, one for drive settings. It was elegant, efficient, and gave us a lock button for the mode dial. The G9II separates these controls, which not only robs us of that useful top display (definitely a sad loss) but also eliminates the mode dial lock. That lock is apparently a luxury reserved for true flagships, not mid-tier bodies masquerading as pro cameras. More importantly, separating these functions provides no practical advantage whatsoever. It's change for the sake of change, making the camera larger without adding functionality.

Front custom switch is gone. This one hurts. The G9 had a physical switch in the lower left front corner that I used constantly to toggle silent mode. It was instant, tactile, perfect. The G9II removed it entirely. I've had to remap that function to the red video record button, which is less convenient. Now it brings up a menu that requires an additional button press, killing the immediacy I had before. When you're shooting wildlife or discreet street scenes, those extra seconds matter.

The memory card door lacks the rubber sealing and solid feel of the G9's. After two years with the G9, this feels... cheap. I've gotten used to it, but the first time I opened it, I had that sinking feeling of "did I buy a pro camera or a consumer model?"

Fortunately, the G9II retains the fully articulating screen design I loved on the G9, but bumps the resolution to 1.84 million dots. Honestly? Visually, I can barely tell the difference. This feels like resolution for resolution's sake—nice on paper, imperceptible in practice.

The EVF maintains the same 3.68M-dot OLED panel, but the colors are noticeably better—more vibrant and pleasant. It's a subtle but welcome improvement that makes the shooting experience more enjoyable.

The G9II uses the new DMW-BLK22 battery, which is backward compatible in one direction only: you can use it in the old G9, but the old BLF19 won't power the G9II. The new cells have higher capacity, and the market is already flooded with third-party versions featuring built-in USB-C charging ports—a genuinely useful innovation that lets you charge batteries directly without a separate charger.

With all the features Panasonic removed or relocated, you'll spend your first week re-mapping buttons and building custom menus. The G9II's "My Menu" system is robust enough to partially compensate for the missing physical controls. I created a custom page with:

- Silent mode toggle

- Focus mode selection

- ISO limit settings

- Stabilization mode options

This helps, but it's a Band-Aid. A physical switch will always beat diving into menus, no matter how well-organized. The camera does allow you to assign functions to 10 different buttons/dials, but you'll find yourself sacrificing some assignments just to replicate basic G9 functionality. My advice: spend a day configuring before your first serious shoot, or you'll be fumbling when it counts.

Practical Performance: Beyond the Spec Sheet

Numbers are one thing, but how does the G9II actually perform when you're pushing it? The headline 60 fps with AF-S sounds impressive, and it is—I've captured hummingbird wing beats I never could before. But here's what matters: the buffer. The G9II will swallow 200 RAW frames before slowing down, compared to the G9's more modest 50-frame buffer. This means you can actually use those high frame rates without immediately hitting a wall.

Fast Serial shooting with pre buffer, that shoots before you press shutter button (1.5, 1 or 0.5 seconds long) is still there. Useful, easily activated, good.

Start-up time is another story. The G9II is slow on initial power-up—around 2.5 seconds from cold start to ready. That's frustrating when something unexpected happens. Once it's asleep, wake time is under a second, but if you fully power down to save battery, you'll miss spontaneous moments. I learned to just leave it on and trust the improved battery life.

Battery performance is rated at 390 shots per charge (CIPA), which is conservative—I regularly get 600+ in real-world use.

Autofocus: Finally, Phase-Detect Arrives

Panasonic finally caved and added phase-detect autofocus to their hybrid cameras, pairing it with their native DFD system. The marketing claims this dual system delivers unprecedented speed and accuracy. But what's the reality after months of shooting?

In single-shot AF mode, I honestly can't tell the difference from the G9. It's just as fast, just as accurate. With all the detection modes disabled and just straight single-point AF, there's no perceptible improvement. The only exception I noticed is with my Panasonic Leica 50-200mm lens—it gave me slightly more focus errors on the G9, and those have completely disappeared on the G9II. But that's the only lens where I've seen a difference.

The intelligent detection modes are now separated by subject type, and you can't enable them all simultaneously. You have to choose: People, Animals, Vehicles, Motorcycles, Trains, or Airplanes. Each has two modes—general detection (full figure) and priority on critical details (eyes for people).

What I loved about the old system was its universality. It would catch cats, dogs, goats, monkeys, birds—even fish sometimes! It was gloriously indiscriminate. I was worried that splitting them up would make the system less versatile. And you know what?

I was wrong. Animals are detected like they were - any animals. Sometimes you need to switch between humans and animals. But it did not spoil the hhow.

That said, when you actually use the detection modes, they're noticeably smarter. Human face detection works at astonishing distances—I'm talking "is that even a person?" far. Better yet, unlike the G9, the G9II doesn't get confused when someone closer to the camera turns their back. It stays locked on your intended subject instead of jumping to the nearer person's head. That's genuinely impressive and saves countless frustrating moments.

Continuous AF: The Real Winner

Here's where phase-detect makes its presence known. AFC performance has improved dramatically—no more of that micro-wobble that plagued DFD in challenging conditions. Tracking accuracy is better, and misses on subjects moving toward you are almost nonexistent now. Everything stays in focus, which is a massive relief for action shooting.

Tracking AF with eye detection is similarly enhanced. Once it locks onto an eye, it stays there through movement, brief obstructions, and changing lighting. It's not perfect—no system is—but it's a legitimate step up from the G9.

The Missing Features That Hurt

But Panasonic giveth and Panasonic taketh away. Two incredibly useful features have vanished: Post Focus and in-camera Focus Stacking. These were tied to the 4K/6K Photo modes, which themselves are completely gone. I occasionally used the in-camera focus stacking feature on the G9—it was brilliant for macro work. The camera would rattle off a series of shots at different focal points and automatically blend them into a single, perfectly stacked image.

The G9II can still do focus bracketing, but you're left to manually stack the RAW files in post-production. Let me be clear: manually stacking dozens of macro shots is not something I ever want to do. It's tedious, time-consuming, and requires specialized software. This feels like a major loss for a camera marketed as a universal instrument.

And still no in-camera panorama stitching—a feature even some entry-level cameras have. The new processor could handle this effortlessly, but Panasonic remains stubbornly against it. These in-camera conveniences are what make field photography more efficient, and their removal is disappointing.

LUT: Fancy Filters or Real Innovation?

So what did we get instead of those useful features? LUT support through the Lumix Lab app. Look, I appreciate the effort, but this feels like a very questionable trade-off.

A LUT (Look-Up Table) is a mathematical file that transforms color values in your images. In photography, it's essentially a finishing style—a filter, if we're being honest. You can create these styles on your smartphone and load them into the camera, but they only apply to JPEG files. So you're "baking" a filter into your image at capture, which feels suspiciously like Instagram filters for camera nerds.

The idea is that you can create a custom look, see it in real-time through the EVF, and share stylized images instantly. But here's my problem: as a photographer who shoots RAW, the idea of committing to a look in-camera feels backwards. I want maximum flexibility in post, not a pre-baked creative decision I might regret later.

In my opinion, LUTs are more of a toy than a serious replacement for features like in-camera panorama stitching or focus stacking. "Baking" filters into JPEGs is a questionable pleasure—especially when you could achieve the same result with better control in post-processing. Maybe I'm just too old-school, but I don't see the appeal.

That said, if your workflow demands quick turnaround—shoot, transfer to phone, publish—then LUTs might make sense. Wedding photographers who need to get preview images to clients during a reception could find this invaluable. For my landscape and wildlife work? Not so much.

The Reality Check: Adoption Rates and Learning

Curious about whether I was alone in my skepticism, I looked into how many photographers actually use LUTs. According to a 2024 survey of professional photographers by Aftershoot, while 73% have experimented with LUTs, only 23% use them regularly in their professional workflow. The majority still prefer traditional editing methods, citing greater flexibility and control. Another study from Imagen-AI found that professional photographers who do use LUTs typically maintain a small collection of 5-10 high-quality profiles rather than downloading hundreds of free options.

For those interested in exploring LUTs properly, I'd recommend starting with this comprehensive guide from professional photographer

Wes Shinn: The Ultimate Guide to Cinematic LUTs for Photographers. It covers creation, application, and best practices without the usual marketing fluff.

Image Quality: Steady Evolution, not Revolution

The G9 already delivered excellent image quality, and the G9II doesn't fall behind. In fact, early firmware issues that made G9II files slightly less sharp than the G9 have been resolved—some update quietly eliminated that problem. Whether it was moiré suppression or phase-detection point masking, I don't know, but current output is crisp and detailed. As always with Micro Four Thirds, you need excellent glass to see what the system can truly do—budget lenses won't show you what this sensor is capable of.

The G9II uses a "dual output gain" sensor design similar to the GH6, which Panasonic calls "Dynamic Range Boost." This essentially reads each pixel at two different gain levels simultaneously and combines them for better highlight retention and shadow detail. The result is cleaner files at base ISO and noticeably better highlight recovery than the G9.

Another technical improvement: the G9II can shoot 16-bit RAW files at base ISO, not just in HHHR mode. This gives you more tonal gradation in skies and smoother shadow transitions. You won't see this in normal shooting, but when you push files in post, that extra bit depth matters.

And yes, you finally get true ISO 100 (not "Low ISO") with full dynamic range, thanks to that DR Boost system. The G9's ISO 200 base always felt limiting for bright scenes.

More Megapixels: Welcome, But Not Essential

The bump to 25 megapixels from 20 is welcome. I tested this when the G9 launched—20MP was the minimum where you wouldn't feel pixel envy. Moving away from that edge gives more cropping flexibility and better detail rendering, especially with high-quality lenses.

The original G9 had a subtle weakness: a red channel bias that revealed itself in extreme shadow recovery. In normal shooting, you'd never see it, but when pulling up deep shadows by 4-6 stops (those "stupid tests" we all do), you'd get a slight red tint in the lifted areas. Not a deal-breaker, but annoying. The G9II eliminates this entirely—shadows lift clean and neutral.

The G9's practical ceiling was ISO 6400. At this sensitivity dark sky, after being denoised, gains minimal color fluctuations. Beyond that, even the best noise reduction couldn't salvage them.

The G9II pushes that ceiling one stop higher—ISO 12800 is now the absolute limit where you can still produce a decent image with careful processing. This matches my definition of usable: not clean, but workable in a pinch.

I must say, the DXO works differently with files from G9 and G9-II... Files from G9 appear best when denoised by PRIME XD/XD2 algorithm. G9II's files are just destroyed by this algorithm - all the details are gone. With G9II files it's better to use Deep Prime algorithm, not XD/XD2 - it gives better results.

But here's the frustrating part: Panasonic removed iAuto ISO, a feature I used constantly. Standard Auto ISO is now your only option. The difference? iAuto analyzed scene motion and, if nothing was moving, would increase shutter speed beyond your set limit to keep ISO lower. It was smart. The current Auto ISO is the "dumb" algorithm: "Shutter speed below limit? Raise ISO." It doesn't care if the scene is static, if you have stabilization engaged, or if you're on a tripod. As someone who often shoots static landscapes handheld, this feels like a needless downgrade.

Image Stabilization: Still Industry-Leading

The G9's stabilization was already legendary, and the G9II maintains that crown. The 8-stop Dual I.S. 2 system is borderline witchcraft. I've handheld the Leica 100-400mm at 400mm (800mm equivalent) at 1/15s and gotten sharp shots. For static subjects, you can shoot multi-second exposures handheld—I've done 4-second shots of cityscapes at night that are tack sharp. It opens possibilities that would require a tripod on other systems.

The system works by combining sensor-shift and lens stabilization, and it's so effective that I often leave my tripod at home for day hikes. For a photographer who values mobility, this is arguably the G9II's killer feature.

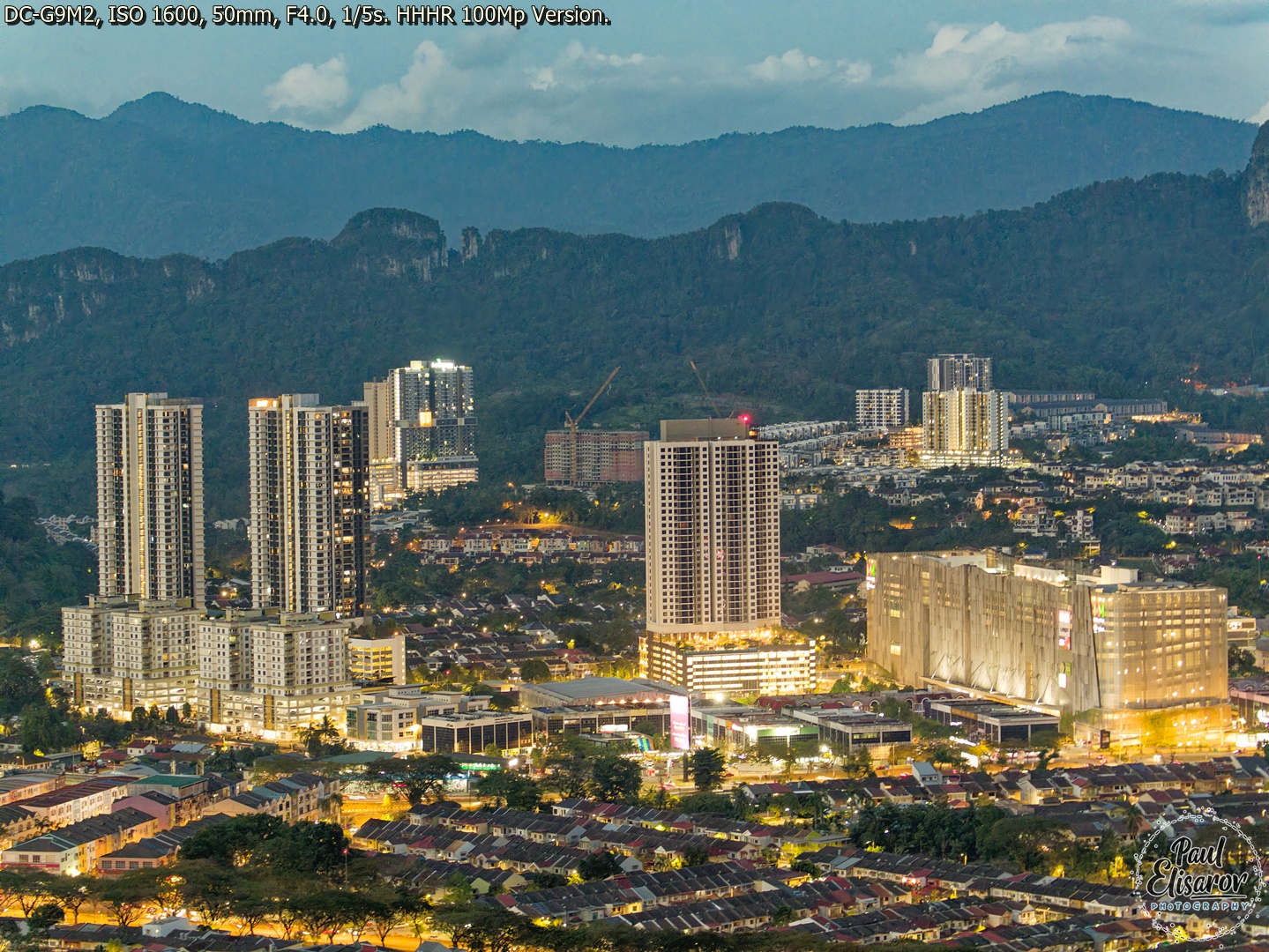

HHHR: The Hidden Gem

Special attention must be paid to HHHR (Hand Held Hi Res) mode. This feature, shooting from the hand, creates a single 100MP RAW file. That's right—one hundred megapixels. It's a composite of eight frames captured in rapid sequence. As the name implies, you get a high-resolution file with motion suppressed—moving objects appear once, not multiple times, unless they're moving so fast the camera interprets them as separate objects. But does It Actually Deliver More Detail? I'll let the images speak for itself:

This is a 100% crop from 25Mp file compared side by side with downsized to 25Mp from 100Mp picture. As you can see - almost NO differences. There is slight increase of details, but not really visible.

But there is another effect in 100Mp HHHR files! Much more important then slight details increase. Let's see another picture:

Look at tiny (on this picture) holes in the round hanging things... On 25Mp picture the color under those holes is dark, almost black. But on 100MP file these holes are red! This shows that 100Mp file has much better color depth and more dynamic range! - more information in such places. And that is a killer feature! It is VERY useful for landscapes if part of the landscapes are badly lit. This eliminates last possible doubt about Micro Four Thirds' dynamic range and color depth. And if you ask me, the resulting 100MP image rivals images from Medium Format in this regards.

As you can see, you don't get a dramatic increase in practical detail. The difference exists, but it's subtle—certainly not the game-changer the megapixel count suggests.

The Real Benefits Are Elsewhere

The true value of HHHR lies in three areas:

Moiré Elimination: On problematic fabrics, architectural details, or any surface prone to moiré, HHHR completely eliminates the issue. It's gone. This alone makes it invaluable for certain types of photography.

Noise Reduction: The noise reduction is significant—I'd call it colossal. By combining eight frames, random noise averages out, leaving you with remarkably clean files even at higher ISOs.

Bit Depth: The HHHR RAW file is 16-bit. That extra color depth means smoother gradients, better shadow recovery, and more latitude in post-processing. And in HHHR file it's used fully, this means basically more flexible photos for you to postprocess.

And you can do this handheld, anytime, anywhere! For some reason, Panasonic doesn't trumpet this feature from the rooftops—they quietly tuck it into the menu. It's the G9II's secret weapon, and once you understand what it really does, you'll use it far more than you expected.

Processing G9II RAW Files: My DxO Photo Lab Workflow

Since I mentioned RAW processing, let me be specific: I use DxO Photo Lab as my primary RAW converter for G9II files. The reason is simple: DxO's DeepPRIME XD noise reduction is unmatched for high-ISO Micro Four Thirds files. At ISO 12800, where the G9II hits its ceiling, DxO can produce results that are very usable.

The G9II's RAW files work beautifully in DxO, with full support for the camera's specific color profiles and lens corrections. The 16-bit HHHR RAWs open with full bit depth, preserving that smooth tonal gradation I mentioned. For regular files, I still get better highlight recovery and shadow detail than Adobe Camera Raw delivers—DxO seems to understand the DR Boost sensor better.

One tip: DxO's "DxO Smart Lighting" tool works wonders on G9II files, automatically recovering highlight detail that looks clipped in other converters. And for the HHHR files, DxO's moiré reduction isn't needed—that's the whole point of the mode—but it does help with the occasional artifacts on fast-moving objects.

Price and Value: The $650 Question

The G9II launched at $1,899 body-only, now a used one can be found for $1200-$1300. Ehile the original G9 now sells for around $1200 new, or $500 used. That's a $650+ difference. Is it worth it?

The G9II is the most capable M43 camera for stills, period. The value calculation comes down to your specific needs. For me, the all the increments in different parts of the camera and the best image quality I ever was able to get from any camera were well worth it. Still, the G9 at current prices is a very effective buy!

With this allow me to conclude this article.

👁

5 views